I’m a fan of a certain warehouse membership club. Sure, I have small complaints like the constant expansion of private label merchandise at the expense of brand choices, or the significant packaging waste that is needed to create the club-specific SKUs. But one thing I don’t complain about is the club’s interest in communicating about specific product safety when risks are identified. In early May CRF Frozen Foods announced a recall of 350 items that were sold in all 50 states and Canada due to a risk of listeria poisoning. I first received a text message, and then shortly after a follow-up letter, outlining the specific items I purchased, and how to return them.

Purchasing a product from any retailer that is later recalled is now becoming more and more likely. The Consumer Product Safety Commission has, on average, issued a recall once every day in 2016, 33 in May, 3 more on June 1st alone. Rather than scary, this increase in recalls is actually a good thing. It is evidence of both a heightened awareness in the need for product safety, and genuine improvement in testing tools and product regulations.

Purchasing a product from any retailer that is later recalled is now becoming more and more likely. The Consumer Product Safety Commission has, on average, issued a recall once every day in 2016, 33 in May, 3 more on June 1st alone. Rather than scary, this increase in recalls is actually a good thing. It is evidence of both a heightened awareness in the need for product safety, and genuine improvement in testing tools and product regulations.

Certainly the pace of recalls of promotional products has picked up, though thankfully, we haven’t yet earned the scarlet letter of our own category on the CPSC website. My experience with frozen vegetables got me thinking—how many recalled items actually are returned? I was glad to know about the recall (which we have talked about before as being the responsibility of both the supplier and distributor), but did I really want to save a partial bag, then remember to take it to the store, then stand in line at the returns desk? Knowing how to conduct a recall and communicate it is crucial for suppliers in our industry, and your preferred vendors should share that they have conducted a mock recall as a good business practice. But if you have a recall, and do all the right things—report, communicate, prepare the reverse logistics—how many items will you actually get back? The answer is, despite your best effort, shockingly few. According to a survey of 31 companies with recalls published by Kids In Danger, only 10 percent of products could be accounted for, and only five percent of consumers returned them into the supply chain. Suppliers in our industry tell me their numbers are even less. Consumers are unlikely to return goods, including those they receive for free as promotional items, because they believe there is nothing wrong (at least that they can see) with the products.

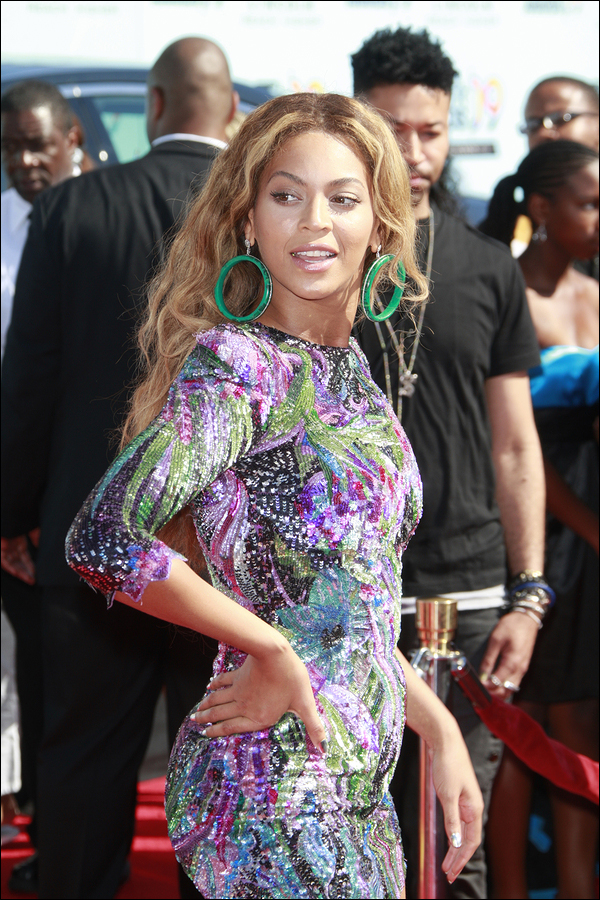

You may have heard about the controversy that started swirling around Beyonce’s new Ivy Park clothing line that is meant to “celebrate every woman and the body she’s in while striving to be better.” Beyonce is being called out because the factories in Sri Lanka manufacturing Ivy Park are labeled as sweatshops. While reasonably few promotional products suppliers currently manufacture in Sri Lanka, the claims are important for us to review.

You may have heard about the controversy that started swirling around Beyonce’s new Ivy Park clothing line that is meant to “celebrate every woman and the body she’s in while striving to be better.” Beyonce is being called out because the factories in Sri Lanka manufacturing Ivy Park are labeled as sweatshops. While reasonably few promotional products suppliers currently manufacture in Sri Lanka, the claims are important for us to review.

Larger end-user clients are very sensitive to the impact socially responsible manufacturing can have on brand image. But this is a perfect example of the need to define what “responsible” means. The Ivy Park factory working conditions reported by the British tabloid The Sun include 10-hour days through the week, and overtime on the weekends, at earnings of only $8.47 a day. An anonymous woman described working in cramped quarters in miserable working conditions, and living in a 10-by-10 room with her sister. “All we do is work, sleep, work, sleep,” she told The Sun for the article. By standards here in the United States, these working conditions would be clearly unacceptable. The irony of a major star appearing to launch a clothing line to lift women up, while at the same time oppressing women manufacturing it, makes for great headlines. But, as The Daily Beast correctly points out in this instance, the lines are not always that clearly drawn. The women working for $380 a month actually far exceed the monthly minimum wage of $202, and the main alternative to work for women in Sri Lanka, and the rest of the Third World is not much better, with many working in the most basic of agriculture.

Arguably, the drumbeat of increased social responsibility in garment manufacturing started with the 2013 collapse of Rana Plaza in Bangladesh that killed 1100 workers. There’s no question the industry continues to put workers at risk, but heightened awareness of end-user clients has forced many factories to protect worker’s rights and pass routine safety inspections. Hopefully, every conversation you have when sourcing garments includes questions about factory conditions before you place an order but, as the Beyonce situation illustrates, you still need to measure those questions against the local norms.

Mushfiq Mobarak, Professor of Economics at Yale University and co-author of a 2015 study in the Journal of Development Economics, “Manufacturing Growth and the Lives of Bangladeshi Women,” told the Beast “We have to ask ourselves: what would these women be doing if they didn’t work in a garment factory? Would their lives be better? Absolutely not.”

Jeff Jacobs has been an expert in building brands and brand stewardship for more than 35 years. He’s a staunch advocate of consumer product safety and has a deep passion and belief regarding the issues surrounding compliance and corporate social responsibility. He recently retired as executive director of Quality Certification Alliance, the only non-profit dedicated to helping suppliers provide safe and compliant promotional products. Before that, he was director of brand merchandise for Michelin. As a recovering end-user client, he can’t help but continue to consult Fortune 500 consumer brands on promo product safety when asked. You can also find him working as a volunteer Guardian ad Litem, traveling the world with his lovely wife, or enjoying a cigar at his favorite local cigar shop. Follow Jeff on Twitter, or reach out to him at jacobs.jeffreyp@gmail.com.